Good / Well part 2

I love this site. http://blog.dictionary.com/

It has nice, short explanations for ESL students to read & understand.

We already have a post about Good vs. Well, but it is so commonly confused (even for native speakers) so I want to share this information from Dictionary.com

You may have been scolded you for saying, I’m good, instead of the more formal I’m well. But is the response I’m good actually incorrect? Not technically. Let’s explore the rules and conventions governing these two terms.

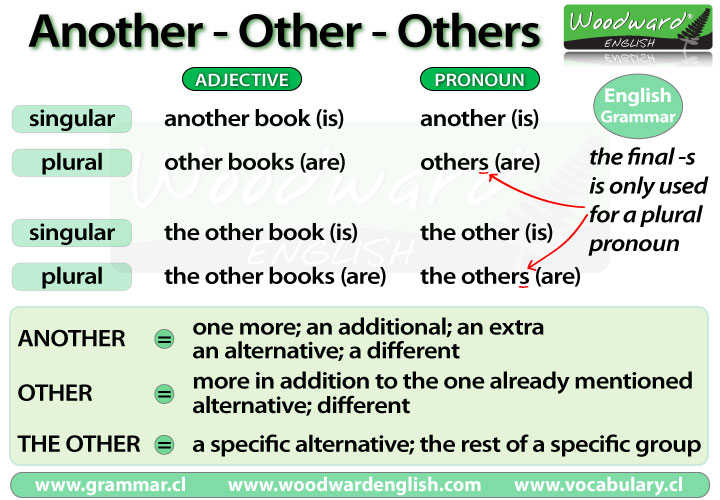

Well is often used as an adverb. Adverbs can modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs. Good is most widely used as an adjective, meaning that it can modify nouns. The expression “I am good” causes some to bristle because they hear an adjective where they think an adverb should be. But adjectives (like good) are used in combination with linking verbs like smell, taste, and look. A linking verb connects or establishes an identity between the subject and predicate, as opposed to an action verb which expresses something that the subject can do. Linking verbs take adjectives, whereas action verbs take adverbs. Think about the sentence: Everything tastes good. It would sound strange to sayEverything tastes well, and the adjectival good is correct in these cases. Typically when well is used as an adjective after look or feel, it often refers to health: You’re looking well; we missed you while you were in the hospital. In general, use well to describe an activity or health, and good to describe a thing.

To go back to common complaint above: in that instance, either good or well work because they both function as adjectives, and that phrase is widely used in informal, colloquial speech. However, in formal speech or edited writing, be sure to use well when an adverb is called for as in He did well on the quiz.

Well gets even more confusing when we consider adjectival phrases like well-known, well-worn, and well-mannered. How do you know when to hyphenate these phrases? Find out in our primer on hyphens.